UX + Agile: A winning formula in complex IT projects

Part I: Task analysis

Earlier this month at the 2017 PMI symposium, we presented a case study about how a Montréal IT firm we collaborate with, Stelvio, integrated User Experience best practices into their Agile cycles. The UX – Agile integration delivered better than expected on product quality, scheduling, and budget on their first of a three-year project—developing an operational software for an aviation company based in Montreal operating in Africa. Seriously, it’s been an amazing project so far.

Between their mastery of Agile & Scrum and ours of User Experience techniques, we all realised that UX is not only compatible with Agile, it actually enhances it by increasing performance, lowering risks and ensuring quality deliverables

This was a high-risk project. Stelvio was asked to create from scratch a complex operating software that would replace the current package their sponsor was using. Moreover, it was the first time Stelvio developed something for the aircraft industry—and saying that aviation software is complex is an understatement. From the onset, all parties agreed the project team needed to understand the aviation company’s processes thoroughly before even thinking of writing code. To that end, they had allotted some discovery and analysis phase ahead of the expected three years of Agile development.

Quickly, Stelvio reached out to us, Yu Centrik, for help. Gaétan, the product owner, sensed that there was a gap between the business objectives this software was to tackle and what the employees were actually going to be doing with this new software. There was no user experience approach, methods, or path of any sort deployed in the project so far. Gaétan had recently done a UX certification for project managers with us, which is why he invited us to accompany them through the project. Getting acquainted with the UX approach and methods filled the gap between the sponsor’s business vision for this software and how this vision should take form in order to be both completely pertinent, efficient and fully usable by employees.

Concretely, Gaétan attributes his success to three UX inputs, namely:

- Task analysis

- A coherent UX design vision and

- Putting people at the heart of every single aspect of the project—yes, using the User-Centred Design approach.

Gaétan is still amazed at how his dev team has adopted the users’ point of view as their own—way beyond applying a given tool or method. The story of how this impacted this project is worth the read, but perhaps a bit long for a single blog entry, so we’ve split it: task analysis here, the other two UX inputs in the next blog.

Are you serious: you want us to do what…?

Task analysis looks in detail at how a task is accomplished, from manual and mental activities, task triggers, technology used, information, necessary interactions with other people, shortcuts, to any other unique factors involved in a given task (Kirwan, B. and Ainsworth, L. (Eds.) (1992). A guide to task analysis. Taylor and Francis).

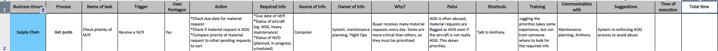

In this case, the task analysis collected 17 different kinds of information to contextualise every segment of every process involved in their work (see image). Those segments were identified by the users we interviewed; each was perceived as a complete step within a task. Gaétan and his team identified hundreds of those steps, and kept 208 to be part of the future software. Gaétan calls these business steps. To illustrate further, task analysis is to functional analysis what prep instructions are to the ingredient list in a recipe. Task analysis presents each step in the sequence they are conducted.

208 business steps x 17 columns of an Excel sheet = a seemingly laborious process of data collection, or so thought Gaétan.

But this became his most trusted, cherished, and concrete UX input. The task analysis anchored each business step in its interconnected context.

This method delivered 2 major benefits:

- First, it allowed to delicately split each task into its relevant steps, ready to be prioritised and scheduled from backlog into sprints, thus making sure what was developed (however small) could be used immediately because it was “whole”; it didn’t lack any crucial feature (nor did it have any superfluous ones in wait of future development).

- Secondly, task analysis also served as a Polaroid of the current (functional, albeit overburdened) ecosystem the new software would have to fit into. Gaétan’s previous experience told him that once the development process was rolling, and new software was gradually replacing the old, the change it entailed transformed work processes enough that the original ecosystem was irrevocably lost. This would lead to a mismatch between the new system and the necessary way of doing things. In this case, Stelvio is replacing with surgical precision the old software & related processes with the new and improved ones—with minimal disturbances in the sponsor’s daily operations (and, in fact, greatly improving these operations).

The business steps help structure their sprints, as they break down into any number of agile stories and story points (from a few to a great many). This articulation allows the assessment of the pertinence (and urgency) of the dimension of each step, making sure coherence and leanness are kept throughout the development. To give you an idea, Gaétan, with his team of 8 developers, plans and delivers about 50 business steps a year. He uses the business steps to do macro-level planning.

At the end of their first year of coding, the Stelvio team was able to deliver a fully usable Minimum Viable Product 6 weeks ahead of schedule, to the delight of the sponsor and its employees. But task analysis could not have made a breakthrough in their dev process on its own—a good UX design vision and strong user-centred approach were key elements to this success, as will be explained in our next blog.

0 Comment(s)